The truth love has taught me.

My love, you showed me how the world really is.

(from one of Amit Trivedi’s very fine original songs from Trishna)

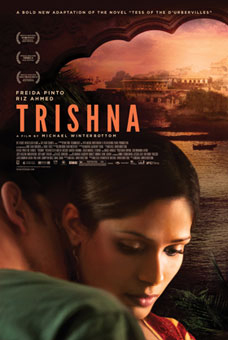

Michael Winterbottom’s latest film, Trishna, is an adaptation of Thomas Hardy’s novel Tess of the D’Urbervilles. Winterbottom, of course, is no stranger to Hardy’s stories, having previously adapted both Jude the Obscure (Jude) and The Mayor of Casterbridge (The Claim). Whereas Jude was a fairly faithful retelling of the book, at least as far as the setting was concerned, The Claim played with the setting, moving it to California during the 19th century gold rush. And such is the case with Trishna, too. Winterbottom retains the essential theme, that of a young woman whose life is controlled by social constraints and the vagaries of fate, but he takes the brilliant step of moving it to modern day India with its social and economic divides, a place where the tensions between rural society and modern cities exist because of urbanisation and industrialisation, and where double standards exist for men and women.

Michael Winterbottom’s latest film, Trishna, is an adaptation of Thomas Hardy’s novel Tess of the D’Urbervilles. Winterbottom, of course, is no stranger to Hardy’s stories, having previously adapted both Jude the Obscure (Jude) and The Mayor of Casterbridge (The Claim). Whereas Jude was a fairly faithful retelling of the book, at least as far as the setting was concerned, The Claim played with the setting, moving it to California during the 19th century gold rush. And such is the case with Trishna, too. Winterbottom retains the essential theme, that of a young woman whose life is controlled by social constraints and the vagaries of fate, but he takes the brilliant step of moving it to modern day India with its social and economic divides, a place where the tensions between rural society and modern cities exist because of urbanisation and industrialisation, and where double standards exist for men and women.

What took me by surprise was that I honestly didn’t expect Trishna to turn out to be my favorite adaptation of Hardy’s work; nor did I expect it to be my favorite of all of Winterbottom’s films. I wouldn’t say I love all of Winterbottom’s films, but I would say they never fail to intrigue me in some way. There’s Code 46, where all sorts of lines are blurred, where language is a mish-mash and where controlling genetic code becomes primordial because genes are also so blurred that people risk not knowing someone they sleep with could very well be a close genetic relative. It’s a film in which the lines between reality and fiction are also blurred, as they are in The Trip, which gives us a slightly fictionalized version of the relationship between the comedians Rob Brydon and Steve Coogan.

Winterbottom’s films frequently have intriguing, challenging portraits of women, often marginalized or transgressive, and for whom things often end badly, whose lives are often ruined by their relationships with the men they become involved with. Maria in Code 46, who is forced into exile. Elena in The Claim, sold by a husband lured by gold. And now, Trishna.

Trishna (Freida Pinto) meets Jay Singh, the son of a wealthy London-based hotelier with business interests in Jaipur, when he and some friends, travelling around India before Jay settles in to work for his father, turn up at a hotel in rural Rajasthan, where she lives. Jay is smitten with the pretty Trishna; he offers her and a friend a ride home, and when Trishna’s father is injured in an accident which destroys the Jeep which is their livelihood, it’s Jay who arranges for Trishna to come to Jaipur to work in his father’s hotel.

Jay is certainly helpful and solicitous towards the young woman, telling her there’s a course she might be interested in, a diploma in hotel management, and offering to give her a couple of mornings off a week to attend it, which she accepts.

But it is clear from the start that Jay has other motives for helping her than simply being kind and supportive. One evening, Trishna’s friends plan on going out after celebrating the wedding of another friend. She decides not to go, and heads back to the hotel on her own. She is accosted by some men, and when Jay happens along on his motorcycle, she accepts a ride from him.

Jay takes her to a secluded spot, kisses her, and Trishna responds to him. We know nothing of what happens after, but we may well suspect, because when Trishna returns to her room, she is distraught. Guilt-ridden, she decides to leave the hotel early the next morning, and returns home to her family, leaving behind a well-paying job. It soon becomes obvious that Trishna is pregnant as a result of her tryst with Jay. In Hardy’s original, Tess has the baby, who dies not long after he’s born. In Winterbottom’s film, Trishna undergoes an abortion, after which she is sent to work at an Uncle’s factory, against her will, as she doesn’t wish to leave home a second time. Home, for Trishna, is a place where she feels safe, a refuge she returns to whenever fate deals her a bad hand.

Jay tracks her down, and gives her another chance at a better life when he brings her to Bombay to live with him, a place where, as he tells her, no one will care if they’re together. Jay dabbles in producing films. Trishna takes dance classes, and hangs out on the fringes of Bollywood, but her life revolves around and is controlled by Jay, who doesn’t want her dancing in movies. The Mumbai section of the film is almost an oasis in their relationship, though. We can almost believe that Jay loves Trishna and that everything will be all right for her from now on, that their relationship just might transcend the class and social issues that could undermine it.

When Jay’s father has a stroke, Jay decides to return to London; before he leaves, Trishna reveals the fact that she’d had the abortion, a revelation that Jay takes very badly. So badly, in fact, that he abandons Trishna in Mumbai without even telling her, simply not renewing the lease on the flat they were living in.

Eventually he returns, though, this time to take over his father’s hotel in Jaipur, arranging to have Trishna work at the hotel and become his personal servant, a job which serves as a cover for their relationship. But it’s a relationship in which the balance of power tips ever more surely in the favour of Jay, and it’s to Riz Ahmed’s credit that he makes me see what draws Trishna to him, even as I want to shake her and make her see what a selfish cad he is, as he grows ever more boorish and dissolute, gradually stripping Trishna of every last shred of her dignity. His actions de-humanize Trishna, and we see it in her face, and in her eyes. Freida Pinto shows us Trishna’s naiveté, her sadness, her suffering, her resignation, and finally, her frustration, unleashed in a final act of desperation.

Here’s the thing: if you’re going to give me an Indian setting, glimpses into Bollywood, songs by Amit Trivedi, and cameos by Kalki Koechlin and Anurag Kashyap, there’s a good chance your film will intrigue me. But it’s one thing to do that, and quite another to make a film that moves me, that is so beautiful visually (frequent Winterbottom collaborator Marcel Zyskind’s cinematography is lovely) and especially aurally – with Shigeru Umebayashi’s elegant score, and dialogues delivered a breath above a whisper – that it makes me feel gutted at the sadness of a young woman’s lot in life, at her vulnerability, and at the only way she can find to take control over her circumstances.

One of the criticisms frequently levelled at Hardy’s work is a frustration with the passivity of his heroine, who, for the most part, accepts what fate dishes out for her, and who does little to assert herself. Winterbottom’s re-interpretation – for it is, truly, a re-interpretation rather than a close adaptation of Hardy’s novel – will do little to dispel that sense of frustration, at least until the closing moments of the film. His Trishna is passive, silent, submissive. But Winterbottom’s re-interpretation is also inventive and thought-provoking. Combining the characters of Angel and Alec into one character, Jay, places the focus squarely on the relationship, which is one of domination and double-standards, with little place for love. Setting the film in India shows us that Hardy’s themes transcend time and place. It throws his ideas into relief, forcing us to re-examine them. It also makes the film brutal and challenging to watch, especially as it progresses.

Where Winterbottom remains remarkably faithful to Hardy’s work is in the arc of his heroine. For Hardy, Tess is a maiden, and then a maiden no more. For Winterbottom, she is, as Jay puts it, three women – the maid, the single lady, the courtesan – rolled into one. And in Winterbottom’s film, as in Hardy’s novel, the consequences remain the same: in the end, the woman pays.