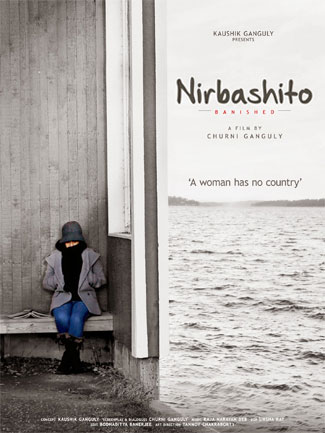

Churni Ganguly’s National Award winning film Nirbashito (The Banished) is both an unflinching and compassionate look at the idea of exile, through the story of a writer, a poet, whose work has so inflamed political sensibilities that she ends up banished from her homeland, forceably torn from her home, moments after fussing over and feeding her beloved cat, Baaghini, which is the last thing she looks at as she is dragged out the door, flown to Rajasthan, taken to Delhi, and from there out of the country, under tight security. Nowhere, it seems, is safe for this writer. Nowhere in India, at least, and perhaps nowhere in the world, as the tight security which her Swedish protectors provide for her once she arrives in Stockholm shows.

Churni Ganguly’s National Award winning film Nirbashito (The Banished) is both an unflinching and compassionate look at the idea of exile, through the story of a writer, a poet, whose work has so inflamed political sensibilities that she ends up banished from her homeland, forceably torn from her home, moments after fussing over and feeding her beloved cat, Baaghini, which is the last thing she looks at as she is dragged out the door, flown to Rajasthan, taken to Delhi, and from there out of the country, under tight security. Nowhere, it seems, is safe for this writer. Nowhere in India, at least, and perhaps nowhere in the world, as the tight security which her Swedish protectors provide for her once she arrives in Stockholm shows.

Those of us who have, perhaps, chosen to live or work or study elsewhere, may connect with the feelings of being uprooted and lost in a country and culture that is not one’s own, but in no way can we feel more than the smallest of connections with what it’s like to be forcibly removed from one’s home, with no belongings, with only a passport, and sent away. Even the writer’s transfer to a secluded home near Stockholm requires security at all times.

“I deserve it,” the writer tells a stunned Lucas Johansson (Lars Bethke), a member of the Swedish Pen Club who act as a support group. “It’s the pen and the sword. The sword always wins.”

Sending someone into exile usually has the immediate and stunning effect of actually silencing them – they can no longer offend, because they no longer have a voice in the culture they have been removed from. This is changing, of course. The internet and social media platforms allow those whose voices have been muted an audience.

In the writer’s absence, the exploration of her by the media falls squarely in the realm of the absurd. While the Swedish Prime Minister is writing a letter to her praising her for her “humanism”, the Bengali press organizes photo shoots of her cat, and asks questions of the wife of a friend (Raima Sen) insisting she comment on the writer’s relationships with men, and rating her looks on a scale of one to ten. But he does ask an incredibly uncomfortable and pertinent question: would the writer be in the trouble that she’s in if she were a man? When the camera pans to a copy of Salman Rushdie’s book Midnight’s Children, we are invited to wonder if this is the answer to his question – if it has only to do with being a writer, an artist, and being someone who challenges our notions and perceptions of things.

The film is dedicated to legendary painter M.F. Husain, who died in a self-imposed exile, to escape what he saw as attempts to curb his freedom of expression as an artist (Husain’s paintings of naked Hindu deities drew the wrath of religious fundamentalists who considered his works blasphemous). But it is, in equal measure, dedicated to Taslima Nasreen – and the film is a somewhat fictionalized examination of Nasreen’s own journey into exile (Nasreen is never named in the film, outside of the dedication). And the film is also dedicated to Nasreen’s cat, Minu — the set of absurdities that surround the writer’s friend, Pritam (Saswata Chatterjee) trying to send the writer’s cat, Baaghini, to her in Sweden only serves to underscore the film’s incredibly serious themes; it also provides a ray of hope in a world that seems so very hopeless for the writer.

Churni Ganguly’s performance of the writer is laden with a melancholy that wraps around her like the smoke from the cigarettes she smokes, especially in moments of deep sadness and frustration. Dark circles under her eyes, her expression of loss is interrupted by rare moments of humour and joy, and occasionally anger. Despite all this she finds herself struggling to write, afraid of losing her own language in a place where she has no one to talk to, trying to preserve it by writing the Bengali alphabet in the snow on a railing. Her frustration grows with each more remote location that she is moved to, and Ganguly does an excellent job of expressing her growing frustration and anger.

Underlying it all, though, is the profound desire for the familiarity of the chaos and colour of her homeland, instead of a life with constant dislocation and disorientation in the starkness, the greyness of the wintry Swedish landscape.

Despite the film’s serious subject matter, it ends on a note of hope and optimism. Nirbashito was awarded the National Award “for its poignant articulation of the suffocation one experiences when exiled in a land that is not one’s own.” We feel the writer’s sense of suffocation, but we also feel the writer’s determination to return home someday, to fight just as hard to return as her beloved Baaghini did to succeed against her own forced exile.