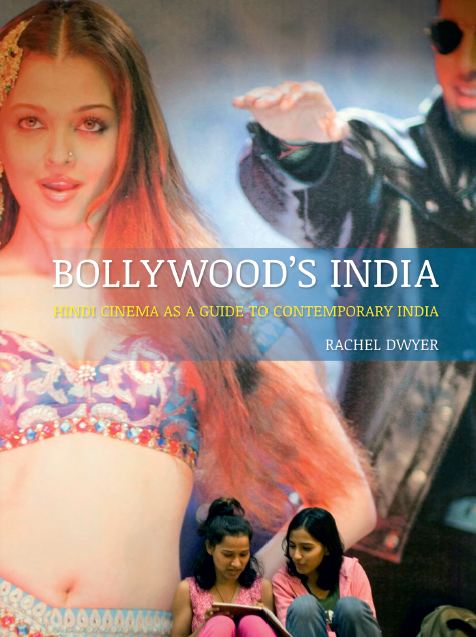

We have a very special treat for all you Bollywood fanatics. BollySpice presents to you an exclusive excerpt from the newly released book Bollywood’s India: Hindi Cinema as a Guide to Contemporary India. Written by Indian Cinema scholar Professor Rachel Dwyer and published by Reaktion Books, Bollywood’s India examines the importance of Hindi Cinema over the last two decades and how it can help us to interpret the social aspects of India as we know it today. Be it religion, human behaviour as well as social, political and economic issues which have affected the country in recent years; Dwyer looks at how all these have been depicted in Hindi films and the important link between films and reality. The book is available to buy now and has also been released in India as Picture Abhi Baaki Hai by Hachette India. This is a must for any movie buff that is curious in obtaining a more critical understanding of Bollywood and its important connection to India as a nation.

We have a very special treat for all you Bollywood fanatics. BollySpice presents to you an exclusive excerpt from the newly released book Bollywood’s India: Hindi Cinema as a Guide to Contemporary India. Written by Indian Cinema scholar Professor Rachel Dwyer and published by Reaktion Books, Bollywood’s India examines the importance of Hindi Cinema over the last two decades and how it can help us to interpret the social aspects of India as we know it today. Be it religion, human behaviour as well as social, political and economic issues which have affected the country in recent years; Dwyer looks at how all these have been depicted in Hindi films and the important link between films and reality. The book is available to buy now and has also been released in India as Picture Abhi Baaki Hai by Hachette India. This is a must for any movie buff that is curious in obtaining a more critical understanding of Bollywood and its important connection to India as a nation.

Rachel Dwyer is Professor of Indian Cinema and Cultures at SOAS, University of London and is the author of numerous publications, including a biography of the great filmmaker, the late Mr Yash Chopra. If you want a taste of what Bollywood’s India has to offer; have a read of this exclusive excerpt which focuses on Hindi cinema and melancholy. Enjoy!

Melancholy and the Artistic Temperament

(N.B. The below excerpt has been published by BollySpice with permission from the book’s author and publisher, Reaktion Books).

While the ‘weepie’ wants the audience to respond physically by crying, melancholy, though often classed as an emotion, is also a mood. Is it associated more with the creative person and also with nostalgia. It is a particular kind of reflective sorrow, often featuring the desire to remove oneself from company, to be alone and thoughtful and creative. Western literature, music and other arts share a long tradition of creative melancholy in individuals (Shakespeare and Keats) and movements (Gothic and Romanticism).

India has many traditions concerning the creative possibility of sorrow, whether this be Sanskrit literature, where love – divine and human – is as much about separation (viraha) and union (sambhoga), or Buddhism, whose founding principles, the Four Noble Truths, are about sorrow. Hindi film drew on the Gothic with its dark and melancholy associations in the 1940s and 1950s, in films like Mahal/The Mansion (dir, Kamal Amrohi, 1949). These emotions have become part of the sensibility of many literary cultures – notably that of Urdu poetry, an important source for the Hindi film lyric, which is often deeply melancholic. The poet’s complaints about unrequited love, the cruelty of the beloved, the loss of honour and faith, public disgrace and thoughts of death can often be read as those of the soul longing for God. It is mostly through these Urdu traditions that melancholy remains present in the Hindi film today, although largely in songs such as ‘Tanhai’/‘Loneliness’ in Dil Chatha Hai, ‘Tadap tadap’/‘Beating’ in Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam (HDDCS)/I’ve Given My Heart, Beloved (dir. Sanjay Leela Bhansali, 1999), or ‘Aaoge Jab Tum’/‘When You Arrive’ in Jab We Met.

Many Hindi films also play on the sorrow of nostalgia – a feeling that now is not the best time, and the past was richer and better, while the future means that even the present will be lost. Many films have looked back on recent decades to search for meaning there that perhaps evokes the India before all the recent changes began, with even gangsters being ‘better’ in the 1970s, when they were still ruled by a moral code, in films such as Once Upon a Time in Mumbai, while Dabangg is nostalgic for the old-style Hindi film, to which it adds many (post)modern twists. In The Dirty Picture, the heroine has a momentary break in her downward spiral of self-destruction when she becomes nostalgic about her past by looking at photographs, allowing her to finally open herself to love, depicted in the song ‘Ishq Sufiana’/‘Sufic Love.’

Nostalgia is often part of the pleasure of the aesthetic of melancholy, which is a creative sadness, not a sadness that makes people weepy, passive and inactive. Melancholy can be a retreat from the demands to be a jolly, extroverted, socially engaged person who tries to avoid introspection. One of the most strikingly melancholic films is Rockstar (dir. Imtiaz Ali, 2011), where the lead character believes he needs to fall in love and experience loss in order to feel the pain necessary to create art. He ends up being angry, behaving badly and suffering, but he is not ultimately depressive as he manages to produce his music, which draws on the Sufi/Islamicate traditions of unrequited love, lost love and the cruelty of the beloved, where the artist is ready to give everything up for his passion. Ranbir Kapoor, one of the few new stars to emerge in recent years, seems to be finding his place as a melancholic, though interspersing this mood with comic moments to give an almost Chaplinesque effect in films such as Barfi! (dir. Anurag Basu, 2012), which was reminiscent of his grandfather, Raj Kapoor – one of the greatest figures of Hindi cinema.

The depressive hero differs from the melancholic hero in that he is doomed by his failure to act. One character who has mythical status in Hindi film is the gloomy Devdas, who first appears in a Bengali novel of 1917 by Saratchandra Chatterjee (1876-1938). This short novel concerns the tragedy of a doomed young couple who are brought down in part by a society that will not let them marry, but also through their own pride and ineffectual behaviour. The film version made by Bimal Roy in 1955 became a classic, although not hugely successful in its day. A remake film in 2002 was launched, as it were, to be the archetypal Bollywood production, and its potpourri of film moments plus a play on star status, excess and visual beauty and a strong musical score meant that the film did well at the box office, even though it had a depressive, suicidal hero who seemed out of step with contemporary heroes. Devdas was not only depressive but also an alcoholic, though the film did not explore mental health in the way that several recent films have (Tere Naam/In Your Name, dir. Satish Kaushik, 2003; Woh Lamhe/Those Moments, dir. Mohit Suri, 2006; Ghajini, dir. A. R. Murugadoss, 2008; and Karthik Calling Karthik, dir. Vijay Lalwani, 2010).

You can purchase a copy of Bollywood’s India: Hindi Cinema as a Guide to Contemporary India from all good retailers, as well as online by clicking on the below link.

Reaktion Books: Click Here