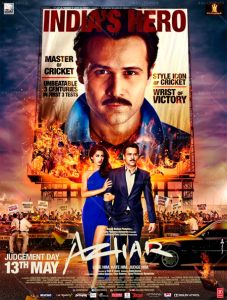

Azhar

Azhar

Starring Emraan Hashmi, Prachi Desai, Nargis Fakhri, Lara Dutta,Kunal Roy Kapoor

Directed by Tony D’Souza

Rating: *** ½

So did he or did he not? Did cricketing phenomenon Mohammad Azharuddin (who fell short of achieving what Sachin Tendulkar or Sunil Gavaskar did) indulge in….ahem…match-fixing? The film leaves us unsure of Azhar’s moral correctness? In building a case of his heroic stature in and out of the sports field, writer Rajat Arora doesn’t flinch from asking uncomfortable questions about Azharuddin career moves and personal choices.

As directed by Tony d’Souza (whose last film Boss was a big bad-ass sambhar-curry) the bio-pic shifts gears from the personal to the professional without tripping on its nose. And that no mean achievement. In making a smooth transition from Azhar’s misadventures on the field to his complicated relationship-status, the narrative shows a level of sensibleness and straight-talking directness that defies the film’s unconcealed bravura ambitions.

Make no mistake. Azhar aims to be a full-on masala version of the real-life sordid tale of a cricketer who was alleged to be as involved in match fixing as in fixing amorous matches for himself. The two women/wives in his colourful life are played by Prachi Desai and Nargis Fakhri, one adequate, the other an unmitigated clueless disaster.

Support for Emraan Hashmi’s sorted and cogent performance comes from some very fine performers. Lara Dutta as the lawyer, once an Azhar a fan now hellbent on seeing him convicted for match-fixing, is sturdy and solid in her courtly avatar. Each time she appears on screen–and that isn’t often enough–she is a knock-out.

And I’d have liked Kunal Roy Kapoor (a watchable and interesting actor) as Azhar’s lawyer-friend without the thick accent and broad mannerisms which leave us in serious doubts as to his capabilities in the courtroom. Like his idiosyncratic gesture of coming his half-bald head, the performance leaves us with little to be actually happy about.

Some very interesting cameos of Azhar’s cricketing colleagues are pitched in by actors who know what they are up to. Varun Bandola’s Kapil Dev and Karanvir Sharma’s Manoj Prabhakar are bang-on. Gautam Gulati’s Ravi Shastri is surprisingly effective. But Manjot Singh (usually so skilled) is unimpressive as the flamboyant Navjot Singh Sidhu.

Some very interesting cameos of Azhar’s cricketing colleagues are pitched in by actors who know what they are up to. Varun Bandola’s Kapil Dev and Karanvir Sharma’s Manoj Prabhakar are bang-on. Gautam Gulati’s Ravi Shastri is surprisingly effective. But Manjot Singh (usually so skilled) is unimpressive as the flamboyant Navjot Singh Sidhu.

The narrative adopts a Kafkaesque game of chess with the black and white pieces playing against one another in a moral fable of no chronological order, as we see the troubled and condemned cricketing icon struggling with memories and muck, trying to make sense of his newly inherited status as a fallen hero. Emraan Hashmi conveys the protagonist’s turmoil with a steady grip on the slippery pitch provided by the cricketer’s controversial past.

Betrayal and a determination to ride the waves of adversary course through the narrative’s virile veins. The footage is edited (by Tushan Shivan) in urgent welters of vivid drama. It’s like watching crucial snatches of footage from a life gone out of control. Not all of it is obligated to make sense to the outsider. The film is handsomely shot by cinematographer Rajesh Omprakash Singh.

Sensibly, the narrative though leaning unambiguously towards Azhar’s non-guilt, does not portray him as a victim and an angel. There are pointed references to Azhar’s need to fulfil an extravagant lifestyle after he fell in love with a high-maintenance movie star. Director Tony d’Souza maintains a firm though flexible hold over the sprawling acres of Azhar’s marshy existence. We see him as neither victim nor villain, neither hero nor casualty….just a successful man whose life is overtaken by circumstances.

Though the time passages are achieved with no real effort to pitch in the periodicity—we are told the court trial stretched into 8 years, but no one shows any sign of wear or tear—Emraan’s emotionally reined-in performance holds the commodious content together. He is particularly effective in showing his hurt when his cricketing colleagues let him down.

Azhar is not an apologetic bio-pic. It doesn’t try too hard to portray the fallen hero as a victim. The director lets the story tell itself out in the hope that the truth will emerge in the process. It does. To a point.