“Love, star-crossed love, being in love with the idea of love, passion and lust — he takes me through his personal repertoire of romance, his voice soft, if a bit gruff at the edges.”

— Madhu Jain on Raj Kapoor in her book The Kapoors: First Family of Indian Cinema

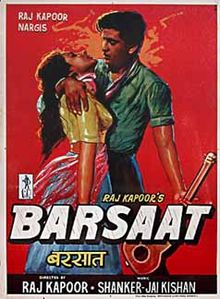

In Barsaat, two rich city slickers, Pran (Raj Kapoor) and Gopal (Prem Nath), go on holiday in the mountains of Kashmir. Pran, the sensitive, poetic one of the pair, meets Reshma (Nargis), and the two fall in love. Gopal, the womaniser, meets Neela (Nimmi), who faithfully waits for him to return during the monsoon season (the Barsaat of the film’s title); the faithless Gopal, however, has no intention of returning, preferring to spend his time galavanting with other women.

Barsaat, really, is a film about love — about a kind of philosophy of love. Pran and Reshma represent true love, love at first sight that hits like a bolt of lightning in a storm of emotion, and that survives any trial or tribulation put in its path. The couple must overcome parental opposition and class differences (Reshma’s father wants to set her marriage to someone in a neighbouring village); accidents (Reshma is washed away in the river when her father, preferring to see her die rather than dishonoured by crossing the river to see Pran, cuts the rope by which she’s secured herself; Pran, obsessed by the thought of Reshma’s marriage, loses control of the car he is driving and is seriously hurt), and the attempt by the fisherman who fishes Reshma out of the river to force her into marrying him. Their love is tested, and it is true, and it finally makes an impression on the faithless Gopal, who realizes that he must finally return to Neela and prove himself worthy of her love.

Barsaat makes most sense if one views Pran and Gopal as two facets of one personality, with two views of love, two experiences of love struggling to co-exist. This would make some sense, too, in the context of Raj Kapoor’s filmography – many of his films are known to be highly autobiographical, and given the level of philosophising in Barsaat, one can’t help but wonder if this was his way of trying to explore and perhaps reconcile these two seemingly disparate facets of his personality — on the one hand, a man who believed in the fundamental truth of romantic love; on the other, a complex personality who needed women as muses, to serve as inspiration, to fuel his creativity.

Barsaat is a troubling film, too, because of its very conflicting views of women: on the one hand, the woman as someone to be worshipped, especially in her avatar of mother — this can be seen when Gopal takes Pran to the woman who is prostituting herself — love can be bought, according to Gopal, but what Pran sees is a woman forced into this situation because of the love she bears for her sick child. Pran gives her money for the child, and he touches her feet.

Yet, women are also shown as potentially faithless: Pran tells Reshma the stories of Heer and Sohni, the implication being that what she should be is faithful like Sohni, and not betray her love, like Heer. The faithful woman as embodied by Neela goes unrewarded, making it difficult to reconcile what is being asked of Reshma. Unless, of course, what is being asked is faithfulness on the part of both partners, in which case it makes sense that Neela’s love is in vain, since Gopal treats her feelings with so little care.

And ultimately, both Reshma and Neela find themselves prostrating themselves at the feet of the men they love — the lover as god, needing to be worshipped, the woman almost begging for love. Sometimes, it’s hard not to think that Raj Kapoor was placing his women on pedestals, only to knock them off them.

That said — Barsaat consolidated Raj Kapoor and Nargis as an on-screen couple, perhaps one of the greatest in Indian cinema. In her book, Jain suggests their on-screen relationship was more than just their obvious chemistry:

“What was important was the way the two balanced each other on screen. They brought out the best in each other, one a catalyst for the other. Raj Kapoor’s searing, at times maudlin, intensity was offset by Nargis’s spontaneity; his clowning by her innate dignity.”

Although Nargis was already a star before Raj Kapoor started putting her in his films, she wasn’t considered a great film beauty. However, “Nargis,” writes Jain, “was never as luminous as when caressed by Raj Kapoor’s camera”:

But from Barsaat onwards there was a subtle transmogrification of the screen Nargis: her face often looks as if it has been lit by the rays of the moon. The camera lingers on her profile, gingerly exploring the landscape of her face, incandescent with an inner glow.

If there’s one thing that is unequivocal about Barsaat: it is an incredibly beautiful film. If you end up with the odd sensation that you are watching something that combined your favourite Hollywood films with those of Satyajit Ray – well, you’re probably not wrong. Raj Kapoor admired Ray’s films, apparently going so far as to ply Ray’s cinematographer with drink and pick his brain about lighting and composition; certainly Barsaat contains an element of intellectualising the concept of romantic love that probably owes much to Kapoor’s desire to create arty films that Jain suggests was equal to his desire to create popular, entertaining films. But Raj Kapoor also acknowledged that much of the camera work in Barsaat was highly influenced by the films of Orson Welles, especially Citizen Kane. The result is a film that is worth watching for the beauty of its cinematography — its lighting, its framing — perhaps even more than for the story itself.