Ilai (Diector. Rajiv Reddy) is a film tracing the journey of a young homeless girl in India, Chennai. As she newly arrives in the choc-o-block, bustling city over packed with traffic and people, she actively tries to make sense of the world around her. Harnessing an innate ability of knowing when to defend and when to chase love, the little girl quickly learns how to carry herself on the bitter sweet streets. She befriends a woman who becomes a mother type figure. Ilai predominantly is an exploration of how the two influence one another to leave comfort zones.

Ilai (Diector. Rajiv Reddy) is a film tracing the journey of a young homeless girl in India, Chennai. As she newly arrives in the choc-o-block, bustling city over packed with traffic and people, she actively tries to make sense of the world around her. Harnessing an innate ability of knowing when to defend and when to chase love, the little girl quickly learns how to carry herself on the bitter sweet streets. She befriends a woman who becomes a mother type figure. Ilai predominantly is an exploration of how the two influence one another to leave comfort zones.

At times, the cinematography will have you spell bound. Artistic shots of the sun and the streets make this film a visual treat: for instance, a particular shot of the heat rising from the train tracks is executed so well, you can feel the heat- an achievement for any piece of art.

The performances are outstanding and natural. The gang of boys on the street held an element of William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, provoking: what would happen if a group of persons were left together on a deserted island? Another question Ilai asks: do dishonesty and manipulation become moral if being used to defend?

Unfortunately, the film is missing an extra element that would have poignantly delivered and summarised the powerful messages being conveyed. It seemed as if much was being stated through symbolism and silence, yet not being brought out fully in potential at times. Some moments did not gel well together and the narrative felt stretched out rather than succinct.

Nevertheless, Ilai is a good exploration of human emotion, survival and regeneration. A key element of Ilai is goodness – the goodness of people, the goodness of love. This was refreshing as very often, films exploring homelessness in India tend to emphasise the bad. True, Ilai does indeed touch on the negative challenges, however the goodness prevails.

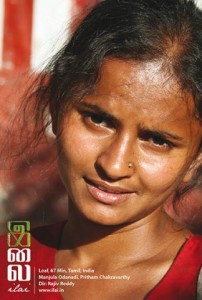

Another element is the fact that love is a universal emotion transcending language. The young homeless girl (Manjula Odanadi) cannot speak the language, yet she communicates with the audience profoundly. The emotion captured in her eyes communicates what she cannot and perhaps will not say. The mother type figure (Pritham Chakravarthy) gives a strong performance reflecting a person who is on the brink of breaking yet holding on.

What the film does not do is delve into any of the character’s back story. This simultaneously gives power to the piece and disempowers the story. The lack of names reflects how the individuals represent everyman characters on the streets of India, therefore forming a collective and powerful message. Nonetheless, the ambiguity causes a void, a rift in rapport for the audience as the direction does not always deliver the connection needed. A back story would have helped to connect with the characters, yet the statement is strong: do we need to know a person’s history to appreciate whom they are?

Interesting to note is that the film ends where it began, in a sunflower field. Effectively, this visual highlights that although the girl has returned to the same destination, she has evolved without her essence being changed. The resonating message conveyed through the protagonist is to not let the journey break you. As the title suggests, the girl drifts like a leaf: whether we choose to see this as freedom or being lost, is at the viewer’s discretion.