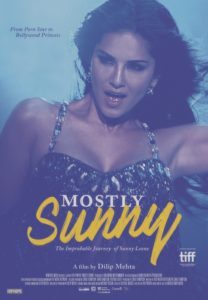

“I don’t know what my legacy will be,” says porn star turned Bollywood starlet Sunny Leone near the end of Dilip Mehta’s documentary Mostly Sunny. Leone acknowledges that her greatest strength isn’t acting, isn’t dancing – it is, as she bluntly puts it, the ability to “turn a quarter into a dollar.”

“I don’t know what my legacy will be,” says porn star turned Bollywood starlet Sunny Leone near the end of Dilip Mehta’s documentary Mostly Sunny. Leone acknowledges that her greatest strength isn’t acting, isn’t dancing – it is, as she bluntly puts it, the ability to “turn a quarter into a dollar.”

Leone is a subject that seems perfectly tailor-made for a documentary about her transition and acceptance – even if that acceptance is frequently grudging – by the Bollywood film fraternity.

Leone’s public persona is documented and well-known. Mehta sets the facts out for us, facts that pretty much anyone with a passing familiarity with Leone knows: that she’s the most searched Indian personality on YouTube; that Osama bin Laden was obsessed with her. “Who doesn’t know Sunny Leone?”, giggles taxi driver Gurpeet Singh Bawa in the films opening moments.

The frustration, of course, is that by the end of Mostly Sunny, we still don’t know much more about her than this, and I cannot decide for the life of me if the fault lies with Mehta, or with Sunny, or, perhaps, with both. It’s true that Sunny Leone has stated she is unhappy with the film, and I can understand that, for the film ends up painting her as incredibly mercenary and occasionally vapid.

The problem with Mehta’s documentary stems, I think, from a number of things, not the least of which is that his subject is incredibly guarded and polished and careful to protect her brand. It’s hard to judge her for that – as she herself says, “… if I was going to take my clothes off for the world to see, then I want to make every single penny. Why should anybody else? That’s what I was good at doing.”

Leone has surrounded herself with supportive people: her brother, Sundeep (whose name she stole for her stage name), her husband and manager Daniel Weber, her costume designer Hitesh Kapopara. Sunny’s drive is clear – she loves what she’s doing, and she just wants to spend as much time in front of the cameras as she can, acting, dancing. That she does neither brilliantly is not the point – she does it as well (and in some cases better) than many of the starlets working in Indian cinema, and the camera, quite honestly, eats her up.

Mehta was, certainly, hampered by the unwillingness of many people connected to Sunny to talk about her. Her childhood, and the reasons why she is, indeed, highly motivated to make money, remain obscure. Her relationship with her brother is, they tell us, close, but at no time do they ever share screen space – most of Sundeep Vohra’s interviews are carried out as he irons his chef’s whites. We get the briefest of emotional insight into how Sunny’s choices have affected those around her, especially her parents, when Sundeep, finally, talks about the death of their mother.

Mehta pads the documentary with filler shots – many of them just street shots of Mumbai at night, often with children – and although they are beautiful, cinematographically speaking, they make little sense in the context of Sunny’s story. He also turns over stones and picks up issues (like the connection of Sunny’s porn past to contemporary rape issues in India) only to drop them as quickly as he finds them. Mostly, the film doesn’t seem to have a point to it: what exactly is Mehta trying to show us about Sunny Leone? With it’s incoherent time-line (even I, reasonably familiar with Sunny’s career, had to go fact-check a few moments) and lack of depth regarding its subject matter, the film fails to form any kind of clear or cohesive whole, a fact that is summed up by watching random people dance randomly for the camera during the film’s closing credits. In the end, it’s all so random.

Director Mahesh Bhatt, who famously met with Sunny while she was contracted to the reality television progamme Bigg Boss, describes her as pretty, as vulnerable, as shy. There is a moment near the end of the documentary, filmed during the shooting of the commercially and reasonably critically successful film Ek Paheli Leela, where Sunny, dressed casually and deglammed, talks about the next scene to be shot – she’ll be dressed as a princess, and she smiles shyly and begins to spin. In that moment, we get the briefest of insights that there is more to Sunny Leone than just Brand Sunny.

In disavowing Mehta’s film, Sunny Leone has affirmed that she believes, now, that only she can tell her own story. I truly hope she finds a way to do that, to give those of us who find her fascinating not only for her transition from porn star to Bollywood star, but also for her ability to understand and value her own worth as a woman, and to take charge of her life in a way that perhaps many would not approve of, but for which she makes few apologies, to give us a chance to really understand what makes Karenjit Kaur Vohra tick.