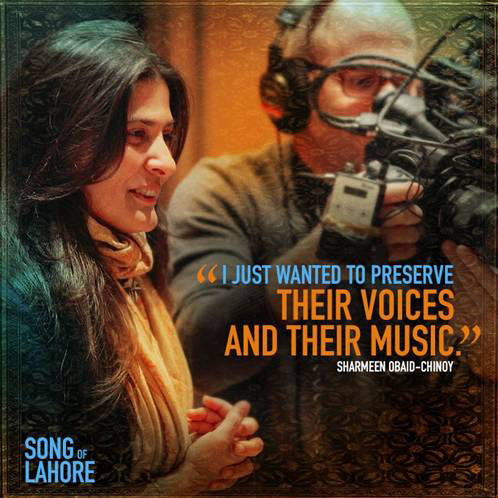

Two-time Academy Award® winner Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy and Andy Schocken bring their acclaimed documentary Song of Lahore to U.S. audiences this Friday, May 20 with a release that includes theaters in New York and Los Angeles plus national availability on DVD, VOD and Digital HD at the same time.

The co-directors sat down for this exclusive interview to discuss their new film which features the music of The Sachal Ensemble of Pakistan and the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis and examines the lives and the cultural heritage of Pakistan’s classical musicians as they prepare for a concert in New York City.

Interview with SONG OF LAHORE co-directors Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy and Andy Schocken:

Q: Was music ever banned in Pakistan?

A: Music was never banned outright, but when General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq took power in 1977 he put in place restrictions on broadcasting non-religious music and dancing. Nightclubs and alcohol were banned, and Zia took steps to shut down the Pakistani film industry, a source of employment for many musicians. At the same time, a more hardline interpretation of Islam became ascendant. As a result, non-religious classical music declined dramatically and musicians lost their former standing culturally, economically and socially. However, even in this oppressive environment, a nascent pop industry grew as a form of protest against Zia’s conservative policies.

Q: After Zia’s reign ended, why did traditional musicians like the members of the Sachal Ensemble still struggle to find work?

A: After Benazir Bhutto took power in 1988, official opposition to non-religious music was overturned. And starting in 1999, under Pervez Musharraf, steps were taken to rebuild the music and film industries. Music grew in popularity, concerts were once again common, and shows on television and radio flourished. However, much of the music that became popular at this time was Western-oriented rock and pop. Opportunities for classical musicians were rare, so many traditional artists had to leave the profession and find work elsewhere.

Q: What are the threats faced by musicians in Pakistan today?

A: After the rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan, and the U.S. military engagement in the region, the situation changed again. The Taliban banned instrumental music and dancing in Afghanistan, and as their influence later crossed into Pakistan, similar efforts were made in areas under their control or sympathetic to their strain of Islam. When fundamentalist religious parties came to power in the Khyber-Paktunkhwa region of Pakistan, they banned public concerts, hundreds of music shops were burned, and a number of musicians and dancers were killed. Many musicians fled the region.

Q: What is the situation like for musicians in Lahore?

A: The situation in Pakistan differs widely from region to region. Lahore experiences limited influence from the Taliban, though hundreds have been killed in terrorist attacks there in recent years. There have been some efforts by outsiders to spread anti-music messages in the city, and there have been some personal attacks on musicians. There are fundamentalist agitators who rally opposition to musicians, claiming that music is sinful. As described in the film, the son of guitarist Asad Ali was attacked and had his keyboard smashed. In 2008 bombs were set off at Lahore’s Alhamra Cultural Center during a musical performance by folk musician Arieb Azhar. Because of security concerns it is rare for concerts to be held publicly. Instead, performances are typically held in private hotels or venues with security guards.

Q: Why does flutist Baqir Abbas speak of having to hide the fact that he and his brother are musicians?

A: In many strata of Pakistani society, instrumental musicians are not seen as respectable. Despite the long tradition of music in Islamic society, conservative Muslims consider instrumental music to be obscene. Musicians are often referred to in derogatory terms, and musical families often hide the fact that they’re musicians, so as not to invite opposition or dishonor. Hence, in the film, we see Baqir Abbas playing the flute with his brother in a soundproof room, so as to not bring dishonor to the family.

SONG OF LAHORE

Release date: May 20 (select theaters, DVD, VOD, Digital HD)

Directors: Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy & Andy Schocken

Music: The Sachal Jazz Ensemble and The Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis

Rating: PG

Runtime: 82 minutes

Trailer:

Official Site: www.songoflahoremovie.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/songoflahore

Twitter: https://twitter.com/songoflahore

SYNOPSIS:

Song of Lahore, the latest feature-length documentary from filmmakers Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy (A Girl in the River: The Price of Forgiveness – 2015 Academy Award winner for Best Short Documentary) and Andy Schocken (The Last Campaign of Governor Booth Gardner), follows the members of Pakistan’s Sachal Jazz Ensemble, a group of master musicians who find international recognition after decades of opposition from dictators and religious extremists. The ancient city of Lahore was once the center of Pakistan’s thriving film-music recording industry, but that came to an end in the late 1970s under the Islamist rule of General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq. Under the conservative regime, instrumental music was repressed, and entire families of musicians lost their livelihood. Music came to be seen as a dishonorable profession, and they found themselves quietly continuing the centuries-old practice of passing down ancient musical traditions from one generation to the next behind closed doors.

As government opposition to music eased in the 1990s and 2000s, businessman Izzat Majeed founded the Sachal Studios Orchestra. He encouraged the group to combine classical Pakistani instruments and techniques with the American jazz he had fallen in love with in the 1950s. Their innovative versions of jazz standards, most notably Dave Brubeck’s iconic “Take Five,” made the orchestra a surprise Internet phenomenon, earning international acclaim and an invitation to perform at Lincoln Center with jazz great Wynton Marsalis and his band. Obaid-Chinoy and Schocken follow the ensemble on an inspiring journey as they struggle to adapt to the unfamiliar strictures of Western music and restore Pakistan’s venerable musical traditions.