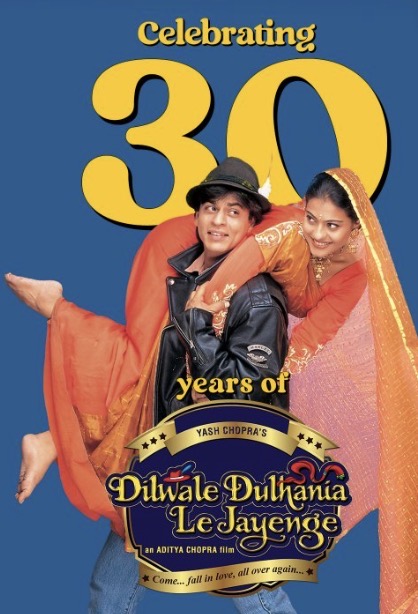

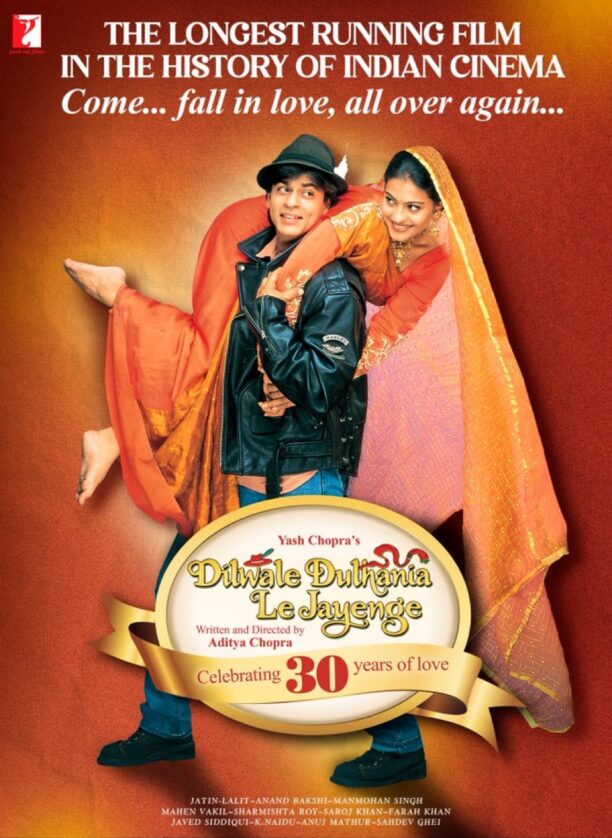

Aditya Chopra’s Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (DDLJ) turned 30 on 20 October. Even after three decades its popularity remains unparalleled. The dialogues, the individual sequences, the songs… they reverberate across the celluloid skyline with primeval passion.

Speaking on the film’s imperishable supremacy filmmaker Vikram Bhatt says, “I have often thought about this. There was a time when I thought, it was perhaps the “meme” qualities of the film like the line ‘Jaa Simran jaa – Jee le apni zindagi’. But on deeper reflection, it is the victory of love through perseverance and not conflict that makes it everlasting. In a culture of eloping this love story says, ‘Only with the permission of elders and our love will seek it out.’ This is heroism of a very different kind and will never be forgotten.”

Hansal Mehta fails to lean into the film’s enduring charm. “I never quite got its enduring charm. Except at first viewing I was quite mesmerised by SRK. Just like I watched only half of Hum Aapke Hain Koun (HAHK). What I did experience though is that it changed the way we titled our films. Before that film titles had a different rhythm. They were short, sharp, and almost literary. Then came HAHK and suddenly every film had to have Dil or Hum in it. Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, Dil To Pagal Hai, Hum Saath Saath Hain, Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam. The word Dil became the mascot of the decade – lucky, commercial, family-friendly. I remember how my film Dil Pe Mat Le Yaar was first called Nau Do Gyarah. But Dil was considered lucky and long titles gave the impression you were making a commercial blockbuster. That’s how the winds shifted! Poetry to packaging, idiom to image, risk to reassurance. My memory is not a very popular one, you see. But it’s mine – shaped not by what the world celebrated but by what it quietly left behind.”

Film critic Rahul Desai attributes the film’s popularity to the blend of the modern and tradition. “Love stories aren’t as novel or popular anymore in the digital age, so everyone likes to know what it once felt like. Same with superstardom and music albums. And it’s also a rare balance of modern and traditional, so there’s something for all sides. For me personally it’s aged well and a reminder of the possibilities of Bollywood back then.”

Critic Sreehari Nair zeroes in on Shah Rukh Khan as the DDLJ’s driving force , “I think Shah Rukh Khan’s is a performance that spoke to that bunch that watched the movie in 1995, but it’s also a performance that anticipated a lot of the styles and mannerisms that were later popularised by the American sitcoms of the 90s and 2000s, and the sort of performance can hold its own even in this age of reels and memes. The movie is probably a time-capsule but Raj Malhotra renews himself for every generation.”

Nair also draws attention to the work’s technical finesse, “DDLJ is technically far more astute than people realise on a conscious level. For example, at the end of Mere Khwabon Main Jo Aaye we see Kajol falling on the ground in the rain and the next shot we get a match cut of Shah Rukh Khan lying in a pool. There are many such examples.”