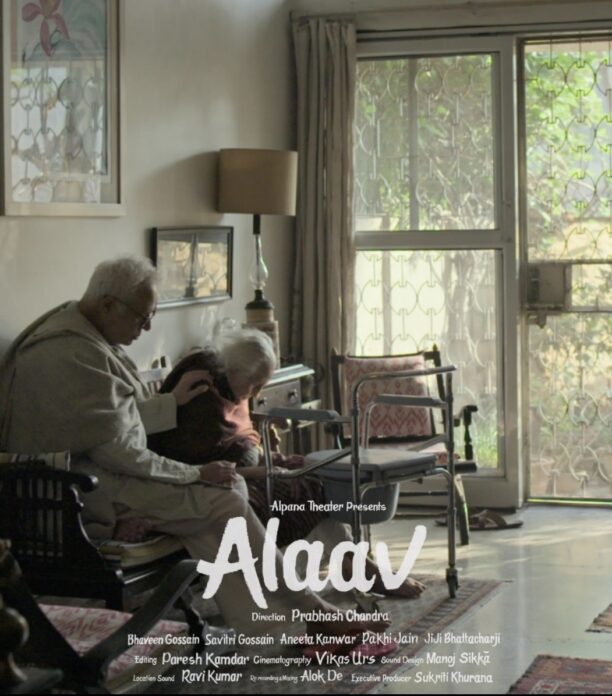

It is hard, very hard, to describe what writer-director Prabhash Chandra has attempted—and succeeded in doing—in Alaav. This is not just a film. It is the closest I’ve seen a film come to realism. And yet this is not a documentary, though both the principal characters, the son and the mother, are played by real-life son-mother Bhaveen Gossain and his nonagenarian mother Savitri Gossain, though I wonder if “played” is the proper word for what the two have done in Alaav.

It is hard, very hard, to describe what writer-director Prabhash Chandra has attempted—and succeeded in doing—in Alaav. This is not just a film. It is the closest I’ve seen a film come to realism. And yet this is not a documentary, though both the principal characters, the son and the mother, are played by real-life son-mother Bhaveen Gossain and his nonagenarian mother Savitri Gossain, though I wonder if “played” is the proper word for what the two have done in Alaav.

Prabhash Chandra takes the two lives of the frail mother and the caregiver son and weaves them into a two-hour meditation on mortality with endless stretches of silence accentuating Bhaveen’s almost complete dissociation with life outside his home. Even when there are the random guests—students who arrive to imbibe musical and scholarly gyan but hurriedly leave with excuses—there is no respite.

Bhaveen doesn’t welcome guests. Not even Rita, who clearly has a soft corner for Bhaveen and vice versa. The only relief for Bhaveen from the tireless tedium of caregiving is Rita’s visit, where, in her broken Hindi, she gently makes plans for both of them for after… You know, after.

Bhaveen’s commitment to the ennui of caregiving is unbroken by hope: he clearly lives in the moment. There are long stretches in the unadorned narration when Bhaveen is seen patiently feeding his mother, cajoling her to eat, and coaxing her to defecate with equal rigour. This one is not for the idlers.

Alaav is one with its protagonist. As the audience, we are not spared any of Bhaveen’s unbroken routine with his mother. Why should we be exempt from the endless exertion?

Alaav is the opposite of escapist cinema. It births a new kind of cinema on death: the anti-escapist cinema where every breath is unrehearsed, every breath is a blessing… at least that is the effect that Prabhash Chandra aspires to create.

There are no extraneous sounds or movements in the narration beyond the caregiver and the receiver, and their mutually cloistered world, where the overhead sound of an aircraft is a reminder of life outside. The bond between the two is umbilical. Bhaveen speaks to his mother as though she is a baby: aa karo, ninni aaye, susu laga….

It is a thankless job, and yes, there are bouts of rage at the sheer unremittingness of the son’s duties. Prabhadh Chandra captures the terrifying isolation of the caregiver without pause or diversion. This is not a film. It is not a documentary either. I don’t know what it is.