100 Years of Satyajit Ray: a tribute to The Apu Trilogy

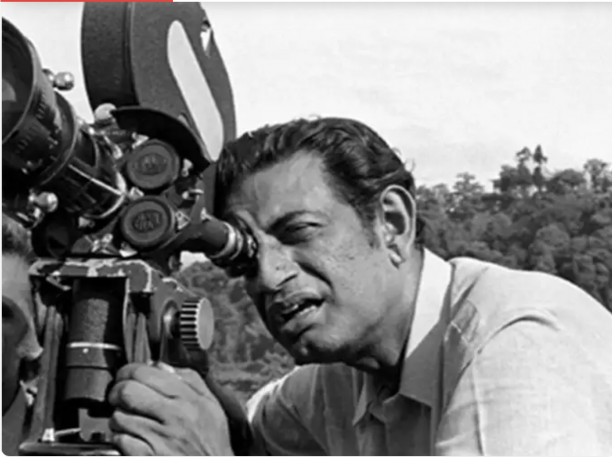

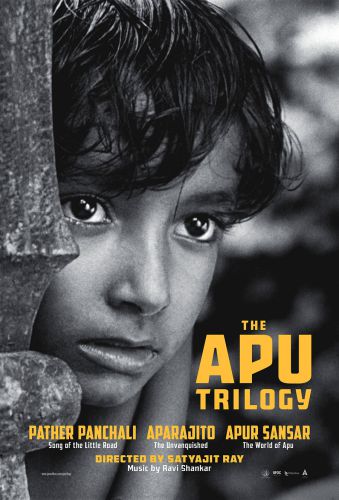

May 2, 2021, saw the start of celebrations of the 100th birthday of the great Bengali filmmaker, Satyajit Ray. Ray’s films were probably amongst the earliest Indian films I’d seen, long before Bollywood would grab my attention. I love many of Ray’s films: Devi from 1960 (starring the sublime Sharmila Tagore) is a particular favourite, and is a commentary on religious devotion and fundamentalism, and, particular, on a system that both places women on pedestals as goddesses even as it removes their agency and represses them. Charulata (apparently the film Ray himself cited as his own favourite of all his films) is an exercise in subtle storytelling and gave us the irrepressible Amal, played by Soumitra Chatterjee, who literally stole my heart in so many films. But no Ray film touches my heart so completely as do the three films in the Apu Trilogy: Pather Panchali, Aparajito, and Apur Sansar.

May 2, 2021, saw the start of celebrations of the 100th birthday of the great Bengali filmmaker, Satyajit Ray. Ray’s films were probably amongst the earliest Indian films I’d seen, long before Bollywood would grab my attention. I love many of Ray’s films: Devi from 1960 (starring the sublime Sharmila Tagore) is a particular favourite, and is a commentary on religious devotion and fundamentalism, and, particular, on a system that both places women on pedestals as goddesses even as it removes their agency and represses them. Charulata (apparently the film Ray himself cited as his own favourite of all his films) is an exercise in subtle storytelling and gave us the irrepressible Amal, played by Soumitra Chatterjee, who literally stole my heart in so many films. But no Ray film touches my heart so completely as do the three films in the Apu Trilogy: Pather Panchali, Aparajito, and Apur Sansar.

I could tell you all sorts of things about the Apu Trilogy that you’ll no doubt have read elsewhere: that Satyajit Ray was inspired, most particularly, by Italian neo-realist cinema such as that of Vitorio di Sica, whose Lladri di biciclette (Bicycle Thieves) is a film that makes me weep, no matter how many times I’ve already seen it; that it was based on two works by Bengali writer Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, which Ray eventually adapted into the three films of the trilogy; that the trilogy forms a bildungsroman (a coming of age story), focussing on the life of Apu; that the film is visually beautiful but is also languorous and winding and requires patience on the part of the viewer.

I could tell you that Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road, the first film in the trilogy) was critically acclaimed, that it won the National Award for Best Feature Film in 1955, and the Best Human Document award in Cannes in 1956; that Ray produced a masterpiece in his first film, though most of his cast and crew was untested – cinematographer Subatra Mitra, for example, had never worked a film camera.

I can say so many things about Ray’s trilogy, but none of them prepared me for the restored version of the whole Apu Trilogy that was released in 2015, a restoration that was undertaken by the Criterion Collection and Janus Films. It took seven years and involved taking Ray’s negatives, burned in a fire two decades ago, and turning them into a beautifully and meticulously reconstructed 4K version. I could tell you, as the press materials did at the time, that “The Apu Trilogy brought India into the golden age of international art-house film, following one indelible character, a free-spirited child in rural Bengal who matures into an adolescent urban student and finally a sensitive man of the world.”

And even if I told you all these things, even if I emphasized how important they are, especially the restoration, all of them pale in comparison to what is truly important here – the story of Apu and his family: Apu’s father, Harirar Roy (Kanu Banerjee), an educated man who longs to earn his living as a writer, who instead earns a meager living collecting rents and through his role as a pujari (priest), and who eventually leaves his family alone for a stretch of many months while he goes to find work in order to provide for them, and to restore his ancestral home, falling into ruins. Apu’s mother, Sarbajaya (Karuna Banerjee), constantly working to keep her family from falling completely into ruin like that ancestral home, a task that proves too much for her in the end. Apu’s elderly auntie (a cousin of his father), Indir Thakrun (Chunibala Devi), who sings the children to sleep, and who is at the mercy of Sarbajay’s taunts until she finally leaves to stay with another relative. Apu’s sister, Durga, with whom he shares many of the joys of life on the worn and dusty footpath: running after the sweets seller; viewing the images in a bioscope, the vendor promising images of the Taj Mahal; enjoying the first refreshing rains of the monsoon whilst sitting under a tree wrapped in Durga’s shawl; hearing a train whistle and running to see a train for the first time.

Courtesy Janus Films

If you think that Satyajit Ray’s masterpiece is only for lovers of black and white, art-house cinema, then I invite you to think again. Pather Panchali is for anyone who has followed the siren call of the ice-cream truck on a summer’s evening; for anyone who has mended a piece of clothing until there is almost nothing left to mend; for anyone who has sold a box of precious and favourite books just to be able to buy Christmas gifts; for anyone who has asked the help of friends and family just to get by another month; for anyone who has stood out in the rain after a stretch of hot, sultry, dry weather, just to feel the freshness of each drop as it falls; for anyone who has lost a friend, or a sister, or a child, or a parent, and who still feels the grief of that loss. Pather Panchali is for all of us. Those folks at Cannes, who awarded the film for its humanity, well, they were on to something there. Pather Panchali documents the human experience, with its struggles and joys. Does it reward us for our patience? Oh, yes. It does.

Courtesy Janus Films

There is a pivotal moment in Satyajit Ray’s film Aparajito (The Unvanquished, the second part of the trilogy): Apu’s mother, Sarbajaya (Karuna Banerjee) descends a staircase, obviously torn by the decision she must make after the death of Apu’s father Harihar (Kanu Banerjee). Should she remain as the cook for the family she has been working for in Benares, happy with her work, even though this would mean taking Apu to Dewanpur? Or should she take up the offer of her uncle, to move to a house he has in the village of Mansapota, where she will at least be sure to be looked after? She pauses on the staircase long enough to watch Apu through a barred window, and it’s at this moment that she makes her decision.

This scene almost sums up everything about her role in Aparajito: the troubles of a mother, alone after the death of her husband, trying to do what’s best, and obviously worried about her future and that of her child. And a child on the cusp of adolescence, where he will learn more about what he wants out of life and will learn to take his first steps alone in the world.

Sarbajaya decides to return to Bengal, to her uncle’s house. The uncle also ensures that Apu can be trained to become a priest, as his father was. Apu does, but he longs to go to school, and Sarbajaya gives in to his begging. Apu, it turns out, is a very good student, and as an older adolescent, he is offered a scholarship to study in Calcutta, where he moves, juggling his studies with work in a printing press (in return for his room and board).

Aparajito reveals a Satyajit Ray continuing to expand his technical skills as a director, and the restored version of the film only serves to underline this, revealing the beautiful camerawork. Ravi Shankar’s score, once again, serves to echo the film’s emotional beat. But Ray’s story is also at the heart of this film, reducing Apu’s family to two, himself and his mother, and thus serving to place emphasis on the nature of motherhood and the relationship between mother and child, particularly as that child grows into adolescence.

Courtesy Janus Films

Apu’s growth as an individual, though, shows him prepared to take decisions about his own future – he knows he wants to continue his studies, wants to study science, and wants to go to Calcutta to do so, a decision he takes before consulting with his mother, telling his headmaster that he will try to convince her. But that need bumps up against that of his mother to look after him. She is thrilled that he’s done well in his studies, happy that he will get a scholarship, but the realization that this will take her son away from her immediately turns her mood. At first, she insists that Apu will not leave, that he will stay and continue to look after her by working as a priest, as did his father. This is the eternal struggle between parent and child: the parent wants the child to stay, the child must break away and find his own way in life. Sarbajaya eventually relents; Apu sets off for Calcutta.

Teen-aged Apu is almost universally recognizable: he is upset when he is tossed out of a classroom, yet he also skips classes. Reluctantly returning home to visit his mother, yet also reluctant to leave her. Spending his breaks sleeping, sleeping, sleeping. Dreaming of travelling, knowing his mother would never agree to it. Writing to his mother, but never as often as she’d like, not knowing that she is keeping her illness from him, even as she begs him to visit her. In one of the film’s most heartbreaking moments, an obviously ailing Sarbajaya imagines she hears Apu returning, and hesitantly makes her way to the door. All she sees are fireflies in the dark, and not even this can ease her sorrow at being alone.

Apu returns home one final time after someone else decides to write to him to tell him his mother is ill, but he arrives too late. The realization – that he has come too late, and that he is now alone — causes him to drop to the ground and begin to weep, all the while calling out for his mother. His great-uncle encourages him to perform the shraddha, the ritual honouring one’s dead parents, and to remain in the village as the priest. But Apu knows that with his mother gone, this place no longer holds anything for him; his road leads him back to Calcutta.

Courtesy Janus Films

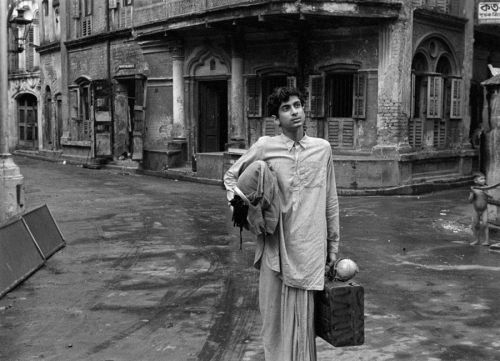

There is a most beautiful moment in Apur Sansar (The World of Apu, final film in the Apu Trilogy) where Apu (Soumitra Chatterjee) stands looking at a sunset. When the camera focuses on him, however, we can see the moonrise over his shoulder. It can’t help but make me think of that famous and oft-quoted phrase of Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa: “The quiet but deep observation, understanding and love of the human race, which are characteristic of all his films, have impressed me greatly. … I feel that he is a “giant” of the movie industry. Not to have seen the cinema of Ray means existing in the world without seeing the sun or the moon.”

This is especially true of the final film in the trilogy, Apur Sansar. In it, Ray gives us an adult Apu – alone in the world after the death of his mother, leaving his studies because he no longer can afford them, searching for other work to sustain him even as he writes a novel.

Courtesy Janus Films

The restoration of The Apu Trilogy was given a limited theatrical release in 2015, and it screened to sold-out cinemas and extended runs. I firmly believe that this is only in part due to the extraordinary restoration work — I truly believe that people everywhere connect with Ray’s films precisely because of that “understanding and love of the human race”, an understanding that travels beyond time and place. Who among us cannot identify with Apu, going for a job, and being told he is overqualified? Who has not been in love, and who has not been heartbroken or grief-stricken at the loss of a loved one?

Courtesy Janus Films

Yes, Ray’s films explore such things as the tensions between rural and urban India, between tradition and modernity. And how else would Apu end up married to his beloved Aparna if it weren’t for a tradition that would see her remain unmarried unless someone stepped up to replace a clearly unsuitable bridegroom? Ray also gives us the incredibly handsome and talented Soumitra Chatterjee as Apu, and the exquisitely beautiful (and also talented) Sharmila Tagore as Aparna, both essaying their first film roles. The screen practically crackles with their chemistry whenever they are together, and they would go on to star in two more of Ray’s films. The best moments in Apur Sansar are those that reveal the days following their marriage, in which they go from being total strangers (what Aparna knows about Apu on their wedding night is only what his friend Pulu has told her) to deeply in love. And indeed, when Aparna dies in childbirth, Apu is so grief-stricken that he blames his own son for her death, turning his back on him to wander throughout India, fulfilling only the minimal responsibility for him by sending money to Aparna’s parents for his care.

And when it looks like Ray will leave Apu, and us, in this state of being totally bereft, something happens. Pulu finds Apu, and manages, somehow, to reach something in him. Apu goes to find his son – Kajal (one of the film’s loveliest moments occurs when Apu and Aparna are talking about her returning to her parent’s home to give birth. Apu asks her what she has in her eye; she responds, “Kajal”, meaning the kohl that lines her eyelids, but it is also a reference to their future son), who is a wild child, naughty and mischievous, and also curious about his father, in that way children are, curious, wanting to know him, and yet angry at him for the rejection he feels.

Apu’s efforts to befriend his son, therefore, are rejected; Apu, we think, is destined to return to Calcutta alone again. But Ray gives us a glimmer of hope – Kajal follows the departing, dejected Apu; when it becomes clear to Apu that Kajal may accept him in a different role, that of friend and not estranged father, he realizes they have a second chance as they set off together.

Courtesy Janus Films

This is an edited version of a piece that was first published at totallyfilmi.com. The boxed set of the restored Apu Trilogy is available from Criterion, and the films are being featured on the Criterion Channel as part of the celebrations of the 100th Anniversary of Satyajit Ray’s birthday.