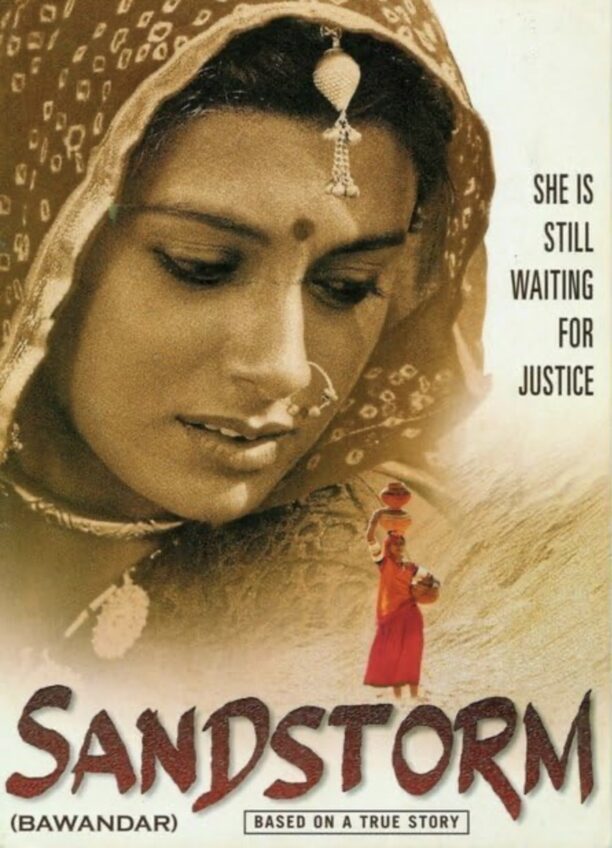

Subhash K Jha focuses on the acclaimed drama Bawandar, which released in 2000.

Subhash K Jha focuses on the acclaimed drama Bawandar, which released in 2000.

I still remember the trauma Jagmohan Mundhra had to go through in trying to release Bawandar.

Nandita Das in what’s possibly the single-most important role and performance of her career , portrays Sanwari with sensitive care. Nandita must be congratulated for projecting the trauma of the rape victim without resorting to breast-beating hysteria. Hers is the best portrayal of the trauma of rape since Tanuja in Tapan Sinha’s Bengali film Adaalat O Ekti Meyi. Then we have Konkona Sen Sharma in Aparna Sen and Applause Entertainment’s The Rapist.

Jagmohan Mundhra’s searing treatise on the real-life gangrape of a Rajasthani saathin Bhanwari Devi (changed to Sanwari Devi in the film) by uppercaste men of her village who couldn’t bear her empowerment, isn’t the first film on rape, nor is it the last. But, Bawandar is a special film. It takes into account not just the trauma of a woman who’s brutalized by a bunch of intolerant elders in her village, it also addresses itself to much wider issues such as the subversion of the legal system, the misappropriation of legal and panchayat–level power and the power-games of the phoney NGOs (led in the film by the ever-brilliant Lilette Dubey) who are savagely satirized by the exiled director Mundhra, who’s come back home from his lowbrow Hollywood experiences with a film that has a great deal of heart and conscience.

All the “ideas” that clutter the captivatingly filmed sand dunes of Rajasthan (and hats off to Ashok Kumar for his vivid camera work) tend to crowd around the main story of Sanwari Devi’s fight to bring her rapists to book. In his effort to bring a sense of telescopic depth to his narrative, Mundhra often disseminates the protagonist’s profound tragedy. But a formal cohesion seems a small sacrifice to make in the light of the larger issues that trouble Mundhra.

There are two subplots in the film about a hugely dedicated social worker Shobha (Deepti Naval)’s brave efforts to keep the faith alive at the cost of her own marriage, and two very glamorous journalists (Rahul Khanna and Laila Rouass) descending on the scene of the crime to piece together Sanwari’s story (a bit of Orson Welles from Mundhra). These fictionalized characters provide a fascinating subtext to the main plot.

Mundhra makes us look at his work as both document and fiction, popaganda and art. Though many of the incidental characters don’t contribute to a cohesive climate, Mundhra bravely sacrifices “the film” for “the truth”. There are long didactic passages of propagandist lectures that take the drama to a pulpit fiction. Also, the dialogues and situations pertaining to the investigation of Sanwari’s rape are not meant for the squeamish. The sequence where the seedy cop (Ravi Jhankal) masturbates into Sanwari’s Ghagra goes a bit too far.

The trenchant film inhabits a world of surcharged authenticity where the characters aren’t accepted to follow rules of socially or cinematically acceptable behaviour. Comparisons to Shekhar Kapur’s Bandit Queen do come to mind. But Mundhra’s film has more colour and music. The glamour provided by the swirling Ghagras and undulating Chunris could have turned the central tragedy into a gross parade of gloss. Mundhra avoids those predictable pitfalls. Where he scores extra points is in dressing Sanwari’s wounds in tender balm. Credit must go to Raghuvir Yadav whose sincere performance as the supportive spouse brings a lump to the throat. His performance in the sequences where he consoles his ravaged wife are the film’s backbone. The other actors are all arthouse regulars cast in predictable postures of authenticity. Deepti Naval as the earnest social worker makes a heartwarming comeback.

Mundhra makes telling use of the music and sounds of the desertscape . Perhaps he could have avoided the aridity that creeps in willy nilly into the storytelling. But the trauma of the main character is as throbbingly real as the rapists’ thrusts which destroy a woman’s selfesteem. Let’s salute this film with a conscience for bringing a real-life story to life without resorting to overt filmy props and perks.