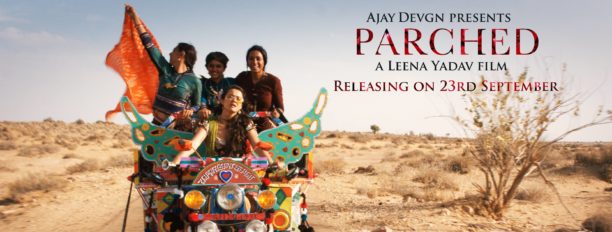

Parched

Parched

Starring Tannishtha Chatterjee, Radhika Apte , Surveen Chawla, Lehar Khan

Written & Directed by Leena Yadav

Long after Parched played out its poignant plot, I kept thinking about the four women at the forefront of Leena Yadav’s sparkling saga of patriarchal tyranny. The enduring grief and the brief bouts of buoyancy that Rani (Tannishtha Chatterjee), Lajjo (Radhika Apte), Bijlee (Surveen Chawla) and Janaki (Lehar Khan) carry with themselves, lingers in our hearts and minds long after the last frame of Leena’s luminous work dies down.

The film is shot with such inescapable beauty by Russell Carpenter (who moves with fluent fecundity from the soggy sappiness of Titanic to the parched desertscape of this walloping work on women’s empowerment) that you fear for the inner lives of the characters. Would their emotional existence be able to withstand the sheer extraneous splendor of the storytelling?

The answer, my friend, is blowing passionately in the winds. The winds of change, if you will. Parched is shot on location in the hearts of a glorious gallery of women who seem to have emerged from generations of oppression and longing into a tremulous, dim yet restorative and nourishing light to claim a place in the blue open skies.

Parched is a melancholic yet sunny meditation on feudal mindsets where women are treated as objects of recreation and contempt, to be used and discarded world. It’s a brutal life for the childless Lajjo who gets thrashed by her sodden husband regularly, for Bijlee the nautanki sex worker who satisfies masculine lustful urges at the drop of a ghagra, Rani a mother at 14 a widow at 17 and now a discarded hag at 35-plus, and tender little child-bride Janaki who is yanked from her parental home and raped by her randy drunken teenage husband (Riddhi Sen, outstandingly loutish) who visits prostitutes, discusses his wife’s breasts with his friends and brags, ‘I am fulfilling my husbandly duties even when I don’t like my wife.’

Significantly, writer-director Leena Das creates two parallel universes for her women heroes. They are crestfallen shriveled dying flowers in their stifling domain of domesticity, but they blossom like summer flowers once together on joyrides in the outdoors, navigated into surreptitious excursions into ecstasy by the feisty Bijlee (whose heartbreaking love story,a Teesri Kasam gone terribly wrong, could have constituted the entire film).

The bustling cosmos that Parched creates comes dangerously close to over-reaching itself. Leena Yadav exercizes enormous control and a profound empathy over the narrative. In this endeavour she is vastly aided by editor Kevin Tent who displays remarkable ruthlessness over the cluttered material, leaving room for not a single superfluous moment.

Parched flows like a child’s tears, unmotivated, unalloyed, unhampered, often without a reason and yet so heartbreaking. It mirrors harsh home truths and dares to delve into areas of rural oppression and gender brutality that are normally not seen to be “relevant” , or seen to be too relevant to matter.

In a sense Parched mirrors the other side of the truth about sexism and the single girl from what we saw last week in Pink. The women in Leena’s film are not sophisticated or urbane enough to fully fathom let alone deal with their horrendous plight. Their sexual oppression goes hand in hand with their sexual innocence. The way these women discuss their bodies and the sex act, or reach out for tenderness to countermand male brutality (I am sure they don’t know the word ‘lesbian’) has never been seen in any Indian film,at least not the ones I’ve seen.

There is also a curious reversal of societal ground-rules where women are often seen to be the worst enemies of their own gender. In Parched all the women share a terrific kinship including Tannishtha’s character with her bed-ridden dying mother-in-law.

Moving and counter-enforcing gender stereotypes, there is a stirring stimulating energetic and erotic energy flowing out of Parched, as though the storyteller decides to pull out all stops to let her women characters speak their minds and act out their innermost fantasies, including one of the female heroes strange visit to a ‘Mystic Baba’ (Adil Hussain, suitably magnetic) who impregnates her. The sequence, a highpoint in the hoary history of female eroticism in Hindi cinema, is shot with a spiritual grace.

Curiously the film’s physical look reminded me of Kalpana Lajmi’s Rudali while its spiritual personality echoes Shyam Benegal’s Ankur specially the preamble where Sayani Gupta in a heartrending cameo, is forced by her parents to return to her sadistic sasural.

A lot of Leena Yadav’s tradition-scoffing narrative works because of her actors. The ever-dependable Tannishtha and Radhika are magnificent. Their empathetic erotic sisterhood is heartbreaking in its desperation. Radika’s comfort level with her physicality is stunningly refreshing for an Indian actress. When was the last time you saw an Indian actress slip out of her blouse facing the camera? Pain and pleasure are often seen sharing a confounding marriage in Apte’s performance. She jolts us with her honest perrformance.

But the real surprise and the firecracker performer is Surveen Chawla. She furnishes her character of the devil-may-care prostitute with a quality of sublime seductiveness and unbridled sassiness. The brilliant screenplay provides Chawla enough meat and she chews on the scenes hungrily. Watch her when she barges into her friend Rani’s son’s wedding and is greeted with sniggering contempt, or that sequence where, slighted by a younger woman’s entry into her seductive domain, she taunts her besotted admirer Rajes h(an excellent Chandan Anand)….Surveen Chawla plays the best whore I’ve seen since Kareena Kapoor in Chameli.

I am not too happy with the way some of the male characters are painted in red, hastily relegated to a brutal zone just to play up the heroines’ stunning sisterhood, which per se is enchanting. In one sequence Tannishtha and Apte egged on by Chawla question all the maa-bahen gaalis and loudly and defiantly shout out their masculine versions.

Yes, the censor board was listening. But there is a different between Anurag Kashyap’s brand of punctuated profanities and the free-flowing rhythms of mischievous stolen furtive kinship shared among women who have never seen better days, and never will.

Parched celebrates the joie de vivre of shared grief among women who live their wretched lives on the edge and are only too happily to topple over when pushed and provoked.

Sometimes, feminism doesn’t need a full-blown messianic clarion call. A little tug, a firm push will do. Parched hits us where it hurts at the most.