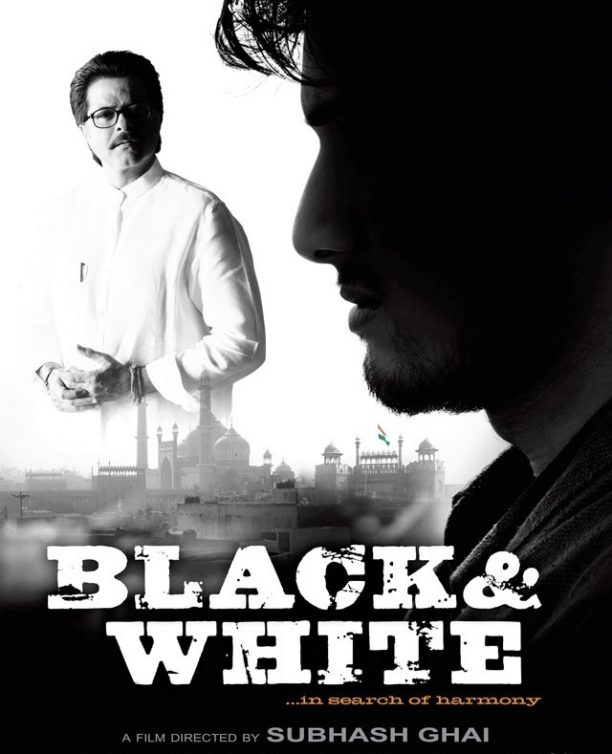

Finally, the truth. Subhash Ghai’s most atypical film Black & White, released on March 7, 2008, was a blatant ripoff of Alan Pakula’s The Devil’s Own. Although Ghai denied the comparison, the similarities are too many to ignore. Subhash Ghai ventures into a territory that would characteristically be considered uninviting for an escapist entertainer.

Finally, the truth. Subhash Ghai’s most atypical film Black & White, released on March 7, 2008, was a blatant ripoff of Alan Pakula’s The Devil’s Own. Although Ghai denied the comparison, the similarities are too many to ignore. Subhash Ghai ventures into a territory that would characteristically be considered uninviting for an escapist entertainer.

It’s a well-crafted, finely written, and packaged piece of cinema done with more heartfelt Gandhian articulations than most recent films, which have merchandized poor Gandhiji in Munna-tones of bubble-gum philosophy.

You don’t often come away from a film disturbed yet hopeful about the distending dimensions of modern-day violence and terrorism. We did it in Mani Ratnam’s Dil Se, Gulzar’s Maachis, and Santosh Sivan’s Terrorist. Now we feel a genuine concern for the collapse of Gandhi’s secular dream in India, as Chandni Chowk (which is rapidly becoming a favourite haunting-ground for Hindi movie-makers) becomes a bustling hotbed of terrorist activities.

Into this arena of imposed constitutional caprices comes Numer Qazi (Anurag Sinha), a victim of atrocities in Afghanistan, posing as a casualty of the Gujarat riots. After a stage-managed gun battle in the toasted-brown hinterland of Delhi, the seething simmering silent Rumer wins over the super-secular Prof Mathur (Anil Kapoor) and his feisty wife Roma (Shefali Shah) and gets himself a pass into the VIP enclave for the Republic Day parade at the Red Fort.

In all honesty, much of Ghai’s newspaper-generated politics is amateurish and simplistic. The terrorists and the intelligence wing look as terrifying and intelligent as an episode of the long-running TV serial CID. And what was the need to make Anil-Shefali’s little daughter mute? Maybe Ghai wanted us to take the Black part of his film’s title seriously.

Everyone bustles around looking brilliantly self-absorbed while pretending to be wedded to a greater ’cause’ of which they seem to know as little as the director. What makes Black & White special is the bondings, brittle or beefy, that form out of the sketchy political backdrop.

Ghai fills the center of the plot with people who have the ability to reach out to each other within a social framework that’s rapidly romancing dementia. Most memorable of all is the old but fiery Muslim poet-professor, played with hungering humility by veteran actor Habib Tanvir. The film’s best and most moving lines are rightfully written for Tanvir.

In one sequence a young musician gifts the old man with a sherwani after having sold his poetry for a song. Habib recalls how in all his years no one, not even his own sons, had gifted him anything…Or that other sequence under a tree where a callow news anchor approaches Tanvir for a bite and he wonders, ‘Ab mujhe kisse bite karna hoga?”

This interesting character’s sense of betrayal for having unknowingly harboured a hardcore terrorist in his house, never comes through.

The screenplay (Ghai, Aakash Khurana, and Sachin Bhaumik) is littered with limp and half-finished loops of storytelling where the director seems to have lost his way, only to quickly get his plot back on its feet through some sharp lines (Ghai’s dialogues are spicy and hard-hitting) and Somak Mukherjee’s cinematography, which captures the quaint kashish, tragic decadence, and teeming colours of Old Delhi to create both romance and intrigue.

The interplay of relationships is restrained most of the time. Anil Kapoor and Shefali Shah look more like a couple than Shefali and Darshan Jariwala did in Gandhi My Father. Her- excessively enthusiastic activism and his chronic embarrassment at his wife’s over-zealous flag-waving provide the lighter moments in this distinctly dark drama of secular devaluation in a society where minority-ism has become a symptom of persecution complexes and complexities.

Ghai doesn’t delve deeply into those complexities—out of choice or because he cannot—we do not know. But the lightness of treatment and the overt filminess of certain interludes (the girl next door falls in love with the scowling terrorist) lend a tangy vigour to what would otherwise have been a drab prosaic and polemical tale of strife during times of mordant cynicism.

Among the performers, Habib Tanvir, with his emotional patriotic poetry and jovial optimism, score the highest marks, followed by Shefali Shah, who furnishes a feisty positivity to her role. Anil Kapoor, seen donning the buffoon’s mask in Welcome does a complete somersault. His character of a supremely secular Hindu devoting himself to teaching Urdu is wildly idealistic. Anil plays Mathur at a high pitch.

As for debutant Anurag Sinha, in the central role of the closet-terrorist he wears the sullen scowl as a ‘passion’ statement from first frame to last. What happened to him?