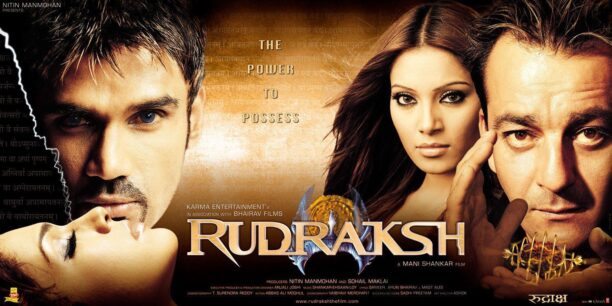

Subhash K Jha revisits Sanjay Dutt’s 2004 Rudraksh, which also featured Suniel Shetty, Bipasha Basu, Isha Koppikar and Kabir BedI in a new installment of This Day That Year.

Subhash K Jha revisits Sanjay Dutt’s 2004 Rudraksh, which also featured Suniel Shetty, Bipasha Basu, Isha Koppikar and Kabir BedI in a new installment of This Day That Year.

You can’t fault this one for not going far enough into the galaxy of untried cinematic experiences. Internet meets antar-atma in Mani Shankar’s fascinating voyage into the flesh of the spirit.

Rudraksh is a full-bodied, robust, and sinuous study of morality. It is our own version of Star Wars (the scenes between Sanjay Dutt and his screen father Kabir Bedi echo George Lucas’ outer-space odyssey), Matrix and The Lord Of The Rings. And if we, the collective critical consciousness of cinema, insist on dismissing Mani Shankar’s thesis on the eternal link between earthly life and the cosmos as mumbo jumbo, then we must also stop raving like imperialistic sycophants each time George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, or Peter Jackson put out a segment of their fuelled fantasies.

Rudraksh compares surprisingly well with these tales of the cosmic dimension. The script embodies the ever-renewable battle between Good and Evil into a fascinating character study. Bhuria (Suniel Shetty) is the modern-day avatar of Ravan, while Varun (Sanjay Dutt), a selfless cool-dude faith healer, echoes the sentiments and ideologies of Rama. Their conflict, so old and yet so new- fangled in its context and treatment, takes the two characters through centuries of moral and spiritual battles fought over a landscape which the director conceives almost like a video game, though the games that the characters play are far from benign.

There are constant changes in time and space, creating an eerie feeling in the viewer of being hurled into eternity, and being caught back from plunging into the abyss just in time. Mani Shankar cleverly links Ravan’s Machiavellian ideology to the communal riots in Mumbai and then to a state of anarchy all over the world.

International terrorism seems to be an abiding concern in Mani Shankar’s cinema. It’s interesting to see the epic dimensions he’s given the theme through computerized effects, first in 16 December and now in Rudraksh, where the protagonist and antagonist battle it out in computer-graphic glory.

In his endeavour to link the spiritual with the sumptuous, Mani goes all-out to simulate the best special effects affordable to Indian cinema. Some of the rugged apocalyptic scenes, especially in the outdoors, evoke the sobering biblical grandeur of Spielberg’s Indian Jones series.

The film’s biggest hurdle to a hefty mass appeal—and it says a lot about the rapidly declining state of our audience’s intellectual threshold—is its often-impenetrable references to Hindu philosophy. Shankar borrows ideas liberally and tellingly from the Upanishads. These, he ambitiously yokes with cyber ideas and hurls them all on screen into a blazing ball of fire.

To dismiss the director’s penetrating attempts at fusing mythology and spirituality with contemporary computer prattle is to undermine the spatial resplendence afforded to the cinematic medium. Shankar makes optimum use of his vision. The screen becomes a manifestation of his subconscious ideology without being snowed under by ideas.

You can watch Rudraksh both as a profound parable on morality as well as a traditional Good Versus Evil yarn. But you cannot, repeat cannot, hope to absorb the film’s multi-echoic philosophy as easy-come-easy-go time-pass entertainment.

Some sections of the narration could’ve invited a more keen participation from the viewers. Throughout, Mani Shankar keeps us detached from the spirit of subjectivity. Hence, the characters never transcend their ideological positions to appeal as flesh-and-blood characters.

The response that comes most often is one of detached admiration. T. Surendra Reddy’s cinematography and Shashi Preetam’s background score are so epical, you wonder why we ape Hollywood when our cinema has the talent to match their best efforts.

Evil has never been done with such ricocheting relish in a Hindi film. We feel its presence every time Shetty’s Ravan appears on screen with his mythical moll Lali (Isha Koppiker). Their love scenes are desperately intense, lustful, and yet lyrical. Both Shetty and Koppiker are riveting in their sinful act and their tragic culmination. It’s rare to see two actors put so much of their body language and inner spirit to such positive advantage in negative roles.

But the film is finally a triumph of Good over Evil. Sanjay Dutt, as the techno-savvy spiritual guru, exudes a magnetic appeal. His long-haired get-up and the questioning piercing eyes make him perfect for the renegade Rama’s role as Munnabhai.

In a rather interesting pivotal part, as the self-serving US-returned research scientist exposing spiritual fraudulency, Bipasha Basu is exasperatingly bogus. She seems more sold on an exposé of another, less spiritual kind altogether. Her facial expressions and body language are becoming exasperatingly repetitive. Not only is she dressed for a dangerous and sinister archeological and spiritual journey as though heading for a rave party, but when she finally gets on the dance floor for the sizzling Ishq khudai dance number (excellent choreography by Vaibhavi Merchant), Bipasha is easily out-rhythmed by starlet Nigar Khan.

Then there‘s the totally out-of-context sequence where Sanjay Dutt gives Bipasha an oil massage. But then I suppose oil’s well that ends well.