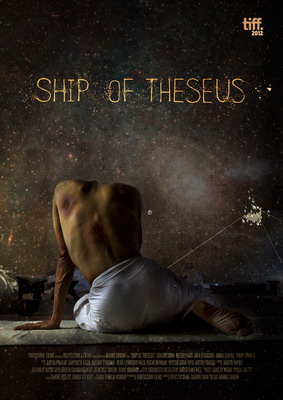

Ship of Theseus is the first feature film from director Anand Gandhi, and, as its title suggests, it explores the philosophical concept of the paradox of Theseus. As described by the Greek philosopher Plutarch, the paradox is this: if an object has any or all of its parts replaced, does it remain the same object?

Ship of Theseus is the first feature film from director Anand Gandhi, and, as its title suggests, it explores the philosophical concept of the paradox of Theseus. As described by the Greek philosopher Plutarch, the paradox is this: if an object has any or all of its parts replaced, does it remain the same object?

The film, then, traces the stories of three individuals, all of whom are affected by this conundrum. Each of them must deal with the change that is wrought in their lives and in themselves either after an organ transplant (in the case of the photographer Aliya and the stockbroker Nivan), or before it (the monk Maitreya).

Aliya (Aida Elkashef) is blind as a result of a corneal infection. Despite this, she works as a photographer, relying on her intuition to fuel her creative output. In addition, she has developed a way of working with her boyfriend – he describes the images she has taken in detail, and she decides, based on what she feels about the experience of taking the image combined with his description, on whether she will accept or reject an image. Images the two of them disagree on get put in something they call a “memory box”, perhaps to be reconsidered another time.

Aliya’s world and her sense of herself as an artist are both changed and called into question dramatically when she undergoes a corneal transplant. When we first see Aliya, she is blind, but incredibly confident, forging into situations without a second thought, making decisions about her art and standing by them. Interviewed during a showing of her work, she reveals the connection she feels with novelist Patrick Süskind’s perfumer – just as he tried to isolate and preserve all the scents in the world, so Aliya wants to isolate and preserve something of her experience and existence through her work.

Süskind’s novel is a story of identity and communication, and Aliya’s sense of identity, and her means of communicating meaning and expressing herself through her photography is called into question after she regains her sight. Aliya is more bewildered by her physical surroundings – she seems to lose some instinctive, intuitive part of herself. The irony, of course, is that Aliya can see, and yet, she can no longer see. Aliya must find new ways of working. Even as she experiences the joy of finally seeing her own photographs, she must confront the new insecurity she feels, and her inability to work and create as she has previously.

Nivan (Sohum Shah) is a young stockbroker who has undergone a kidney transplant. While caring for his grandmother when she finds herself in hospital after a fall, he learns of the case of a patient who has had his kidney stolen (after going in for an appendectomy). Nivan’s initial worry, of course, is that he has been the recipient of the stolen kidney. His research assures him that he has not, but he begins a quest to discover what happened to the kidney, which leads him to confront the existence of illegal organ transplant tourism, and the slippery morality that comes with it. The Swedish man who received the kidney argues that if the owner was willing to sell, then why shouldn’t he buy it? The man himself, so bereft at the loss of his kidney, is mollified when offered a considerable sum of money for it in the end. Nivan questions whether his actions have made any difference at all – and is reassured by his grandmother, who tells him it is always better to try than to remain indifferent. Nivan’s life, his priorities, his morality – even his relationship with his grandmother (an educated woman surrounded by activists, who disapproved of her grandson’s views on life) is transformed after his own transplant and how it calls him to question his life.

Nivan (Sohum Shah) is a young stockbroker who has undergone a kidney transplant. While caring for his grandmother when she finds herself in hospital after a fall, he learns of the case of a patient who has had his kidney stolen (after going in for an appendectomy). Nivan’s initial worry, of course, is that he has been the recipient of the stolen kidney. His research assures him that he has not, but he begins a quest to discover what happened to the kidney, which leads him to confront the existence of illegal organ transplant tourism, and the slippery morality that comes with it. The Swedish man who received the kidney argues that if the owner was willing to sell, then why shouldn’t he buy it? The man himself, so bereft at the loss of his kidney, is mollified when offered a considerable sum of money for it in the end. Nivan questions whether his actions have made any difference at all – and is reassured by his grandmother, who tells him it is always better to try than to remain indifferent. Nivan’s life, his priorities, his morality – even his relationship with his grandmother (an educated woman surrounded by activists, who disapproved of her grandson’s views on life) is transformed after his own transplant and how it calls him to question his life.

Both of these stories bookend what is perhaps the most compelling of Gandhi’s three stories – that of the monk Maitreya (Neeraj Kabi). Maitreya is an animal activist, participating in a trial which aims to see the ending of animal testing in India. When Maitreya finds himself seriously ill, with cirrhosis of the liver, he is told not to worry, there are medications he can take, and he may undergo a transplant.

Maitreya’s first thought, though, is to check his medications on a list of those banned for use because they are produced by companies actively involved in animal testing, and when he finds them there, he refuses treatment. He becomes progressively more ill, more frail – and the film pulls no punches here, showing us his skeletal frame (the actor lost an incredible amount of weight over the course of the shoot), the bedsores that stick to his sheet – but more importantly, it peels back the ethical and philosophical layers he finds himself confronted with.

Maitreya’s first thought, though, is to check his medications on a list of those banned for use because they are produced by companies actively involved in animal testing, and when he finds them there, he refuses treatment. He becomes progressively more ill, more frail – and the film pulls no punches here, showing us his skeletal frame (the actor lost an incredible amount of weight over the course of the shoot), the bedsores that stick to his sheet – but more importantly, it peels back the ethical and philosophical layers he finds himself confronted with.

Maitreya’s character is nicely balanced against that of the young lawyer he works with on the animal testing case. The aptly named Charvaka (after the branch of Indian philosophy that embraces philosophical skepticism) constantly calls Maitreya’s beliefs into question, particularly as the monk comes closer and closer to death. Maitreya’s central belief is one of non-violence (and he is also aptly named, “Maitreya” meaning “loving-kindness”), but Charvaka (Vinay Shukla) wonders about the violence one commits on one’s self by refusing to take medication, and whether sacrificing one’s life for a cause is a huge expectation to place on someone. It’s an expectation that Maitreya seems to set for himself, until he eventually decides his cause would be better served by having him be alive to fight it.

TIFF’s Artistic Director Cameron Bailey has described Ship of Theseus as one of this year’s hidden gems, and it’s not hard to see why. Pankaj Kumar’s cinematography is breathtaking and beautiful. The sound (Gabor Erdelyi and Tamas Szekely) is lush. All the performances are terrific, but the renowned stage actor Neeraj Kabi brings an intelligence and grace to his role that makes his portrayal of the monk particularly troubling and moving.

Ship of Theseus is one of those rare things: an elegant film that demands that its audience be engaged at every moment. It’s an incredibly ambitious film, and if it falters at all, it’s because it, perhaps, asks a little too much of its viewers. Having seen Gandhi’s previous two short films – especially Continuum (co-directed with Khushboo Ranka), with which Ship of Theseus shares much, including a thematic structure and finale – I knew that somehow he would tie the three stories together in a way that was surprising and satisfying. I wasn’t disappointed – but I did wonder what the film was like for those sailing rudderless, not sure where the Ship of Theseus was really taking them. The journey is worthwhile, but some judicious editing and a better sense of continuity (Continuum, for example, used title cards to express which concept we were seeing played out in each of the stories) would make this film the truly magical, mystical voyage it is meant to be.